THE ARTIST, HARRY PYE By Neal Brown

Harry Pye

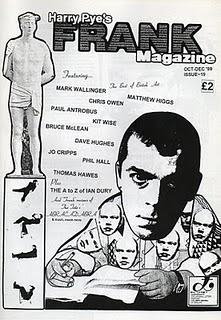

Harry Pye is a rotund, bald, male artist and writer who has humbly worked at the bookshop of Tate for endless years, and who occupies a place in the art world that might be described as marginalized. His corrective for this indignity – apart from general good grace and acceptance – is, quite sensibly, to place himself, fabulously, and with trusting optimism, in the centre of his work. After years of being a humble art world fanzine editor – the excellent Frank Magazine (1995-2000) – and interviewing famous personages, and making them even more famous, he has now claimed his place as a painter, and is producing fun, droll works, with a lot of singing colour and, most importantly, each picture starring a rotund, bald male in its centre.

Such Pye-centricity has proved to be a recipe for success; the paintings have now become a completely formed vision, and are doing very nicely. As Pye goes up in the world he is now meeting all the people going down, like me, and so I am very glad that I have always been nice to him, and which will always remain my policy, even when I start going up again in the world again, which will be soon, and then Pye and I can both go up together, unless one or the other of us starts going down, of course.

Such Pye-centricity has proved to be a recipe for success; the paintings have now become a completely formed vision, and are doing very nicely. As Pye goes up in the world he is now meeting all the people going down, like me, and so I am very glad that I have always been nice to him, and which will always remain my policy, even when I start going up again in the world again, which will be soon, and then Pye and I can both go up together, unless one or the other of us starts going down, of course.

Frank Magazine

The self deprecating, anxious gag above – about the goings up and down in the art world, and being glad I have always been nice to Pye – is intended to be a representatively Harry Pye style gag, for the purposes of illustration only. (The stylistic context of Pye’s gag making is that of a glorious UK art writing tradition that includes Matthew Collings, Gilbert and George, Billy Childish, Mark McGowan and BANK). There can be lot of sad old pain behind this class of gag making, in which humour replaces sadness to become the crafty vehicle for kinds of truth telling that are usually proscribed – the time honoured subversions of the holy and court fools, carnival madness, and jester and trickster mischief making.

This is all apparent in over a decade of Pye’s Frank magazine, and in his other published writings, which reveal an irreverent, bittersweet sensibility, in which enthusiasm is mingled with a kind of fear; the fear that the philosophically alert (but sometimes sad), underdog has for the powerfully, often vulgarly rich and famous. Rather than attempt a definitive overview of Pye’s writings about the doings of the art world (Pye’s is an huge, many fronted, cumulative project), let this tiny excerpt from a regular series Pye has written for Epifanio online magazine (Epifanio 5, 2006) be considered – by me, not by Pye – representative of the conditions of Pye’s placement within his historical time. It describes a cockroach problem Pye had when he used to live above a restaurant, and his method of dealing with the problem when all other solutions failed;

The poison was very similar to brown acrylic paint. A small amount was put on each door. Apparently the cockroach is attracted to the smell, he rubs himself in it and eats some, goes home, dies, his friends and family then eat him, then they die. Nice.

This isn’t the Harry Pye we know and love, the cuddly, lovable Harry Pye. This is a steely eyed Pye; a pragmatically ruthless Pye who coexists with the other one. This is a quiet avenger of righteous retribution, at whose hands – again, this is my own opinion here, not Pye’s – the art world must, just like the cockroaches, suffer a formidable accounting. Surely, the crazy death system by which Pye’s cockroaches perished is more than similar to the prancings of the art world and its dim collectors, craven critics and insane academics – all engaged in a dark, twilight scurrying and cannibalising of each other’s second-hand ideas and blood plasma. Maybe this is unfair. (It’s certainly unfair to brown acrylic paint; the colour brown has slowly been enjoying a return to fashion with young painters – and means that in eighteen months from now designers will be making brown furniture and lamps again, and in three years brown cars will again be seen on the on the roads . . .)

Whatever. Let’s move on, to Pye’s paintings, which are the important thing. Pye’s paintings are accessible, fun, thoughtful and attractive. They revel in a benign, optimistic message making, based on the bedrock – spiritual touchstone etc – of the previously mentioned sad-old-pain, and whose unfashionable moral positivity points a way out of the repetitions of usual contemporary practice.

This is all apparent in over a decade of Pye’s Frank magazine, and in his other published writings, which reveal an irreverent, bittersweet sensibility, in which enthusiasm is mingled with a kind of fear; the fear that the philosophically alert (but sometimes sad), underdog has for the powerfully, often vulgarly rich and famous. Rather than attempt a definitive overview of Pye’s writings about the doings of the art world (Pye’s is an huge, many fronted, cumulative project), let this tiny excerpt from a regular series Pye has written for Epifanio online magazine (Epifanio 5, 2006) be considered – by me, not by Pye – representative of the conditions of Pye’s placement within his historical time. It describes a cockroach problem Pye had when he used to live above a restaurant, and his method of dealing with the problem when all other solutions failed;

The poison was very similar to brown acrylic paint. A small amount was put on each door. Apparently the cockroach is attracted to the smell, he rubs himself in it and eats some, goes home, dies, his friends and family then eat him, then they die. Nice.

This isn’t the Harry Pye we know and love, the cuddly, lovable Harry Pye. This is a steely eyed Pye; a pragmatically ruthless Pye who coexists with the other one. This is a quiet avenger of righteous retribution, at whose hands – again, this is my own opinion here, not Pye’s – the art world must, just like the cockroaches, suffer a formidable accounting. Surely, the crazy death system by which Pye’s cockroaches perished is more than similar to the prancings of the art world and its dim collectors, craven critics and insane academics – all engaged in a dark, twilight scurrying and cannibalising of each other’s second-hand ideas and blood plasma. Maybe this is unfair. (It’s certainly unfair to brown acrylic paint; the colour brown has slowly been enjoying a return to fashion with young painters – and means that in eighteen months from now designers will be making brown furniture and lamps again, and in three years brown cars will again be seen on the on the roads . . .)

Whatever. Let’s move on, to Pye’s paintings, which are the important thing. Pye’s paintings are accessible, fun, thoughtful and attractive. They revel in a benign, optimistic message making, based on the bedrock – spiritual touchstone etc – of the previously mentioned sad-old-pain, and whose unfashionable moral positivity points a way out of the repetitions of usual contemporary practice.

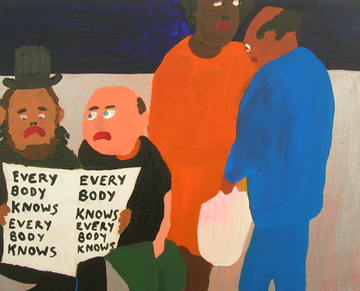

"Everybody Knows" 50 x 60cm 2007

Pye says of Everybody Knows (2007) that, ‘It's about being in Stockwell tube station and seeing a black man who looked exactly like me except black. We are all the same and we are all each other, everyone knows it but we sometimes forget.’ This principle is repeated in his painting With The Muslims (2007) (co-painted with Rowland Smith). The title makes absurdist, parodic reference to a Beatles LP. But, more importantly, as Pye says, ‘It’s saying I am on the side of the Muslims, who are unfairly targeted by media and police. Within the paintings are symbolic representations of good things about to happen and good news about to be told.’ In this way – the way of good news, optimism and joy over experiential pain – there is a kind of evangelism in Pye’s work, which takes sad-old-pain, flings it into the air, and reorders it in a merry derangement.

Pye has an association with the Bart Wells Institute, where he curated the show Viva Picasso (and where, in other shows there, he was probably their most exhibited artist), and he has curated many shows elsewhere. The second show of his own work at Sartorial, the one after Me Me Me (2007), was Getting Better, (2009) which showed him at his collectivist best – Pye says he collaborates because he cannot paint very well, but as many painters cannot paint very well this cannot be the sole reason. A huge number of Pye’s paintings are collaborations, including with Geraldine Swayne, Billy Childish, Kes Richardson, and the already mentioned Rowland Smith, and such collaborations further increase Pye’s reach to his already wildly differing audience base.

Pye has an association with the Bart Wells Institute, where he curated the show Viva Picasso (and where, in other shows there, he was probably their most exhibited artist), and he has curated many shows elsewhere. The second show of his own work at Sartorial, the one after Me Me Me (2007), was Getting Better, (2009) which showed him at his collectivist best – Pye says he collaborates because he cannot paint very well, but as many painters cannot paint very well this cannot be the sole reason. A huge number of Pye’s paintings are collaborations, including with Geraldine Swayne, Billy Childish, Kes Richardson, and the already mentioned Rowland Smith, and such collaborations further increase Pye’s reach to his already wildly differing audience base.

Billy Childish (left) with Harry Pye

The relationship of Pye and Childish may be revealing. In an interview with Pye, for the book Bart Wells Institute (2009), about shows that Luke Gottelier (and others) put on there, Gottelier says to Pye, ‘I’m into this thing of putting people in that don’t really go. Which is partly why you were there at the beginning. That’s why Billy Childish was there.’ Gottelier then explains that he would ask himself, when curating a show, ‘Who’s the one person [I] could put in who’s most unlikely in a contemporary art exhibition?’

As there were not one, but two ‘most unlikely’ persons that Gottelier and the Bart Wells Institute cleverly gave their attention to, this could mean lots of interesting things. Not least that, if they found two ‘most unlikely’ persons, that there may be other ‘most unlikely’ persons about, waiting patiently, elsewhere – currently excluded by curators of the more usual and conformist ‘contemporary art exhibition’ tendency. On this basis Pye should take his most ‘unlikely’ status as a great compliment – he is highly prominent amongst the ‘most unlikely’ artists, and we enjoy full confidence that his time is coming.

As there were not one, but two ‘most unlikely’ persons that Gottelier and the Bart Wells Institute cleverly gave their attention to, this could mean lots of interesting things. Not least that, if they found two ‘most unlikely’ persons, that there may be other ‘most unlikely’ persons about, waiting patiently, elsewhere – currently excluded by curators of the more usual and conformist ‘contemporary art exhibition’ tendency. On this basis Pye should take his most ‘unlikely’ status as a great compliment – he is highly prominent amongst the ‘most unlikely’ artists, and we enjoy full confidence that his time is coming.